- Home

- Paige Bowers

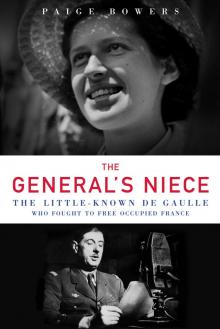

The General's Niece

The General's Niece Read online

Copyright © 2017 by Paige Bowers

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-612-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bowers, Paige, author.

Title: The general’s niece : the little-known de Gaulle who fought to free occupied France / Paige Bowers.

Other titles: Little-known de Gaulle who fought to free occupied France

Description: First edition. | Chicago, Illinois : Chicago Review Press

Incorporated, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016044629 (print) | LCCN 2017003327 (ebook) | ISBN 9781613736098 (cloth) | ISBN 9781613736111 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781613736128 (epub) | ISBN 9781613736104 (kindle)

Subjects: LCSH: Gaulle Anthonioz, Geneviève de. | Women prisoners of war—France—Biography. | Gaulle family. | World War, 1939–1945—Underground movements—France. | Ravensbrück (Concentration Camp) | International Movement ATD Fourth World. | Women in charitable work—France—Biography.

Classification: LCC DC407.G38 B68 2017 (print) | LCC DC407.G38 (ebook) | DDC

940.53/44092 [B] —dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016044629

Typesetting: Nord Compo

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

This digital document has been produced by Nord Compo.

For Avery

Honor is an instinct like love.

—GEORGES BERNANOS

In war as in peace, the last word goes

to those who never surrender.

—GEORGES CLEMENCEAU

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Prologue

PART I: RESISTANCE

1. The Road to Resistance

2. The Call

3. Kindling the Flame

4. Défense de la France

5. Voices and Faces

PART II: RAVENSBRÜCK

6. The Project on the Other Side of the Lake

7. What Can Be Saved

8. Marking the Days

9. Release

10. Liberation

PART III: REBUILDING

11. The Return

12. The Antidote

13. Noisy-le-Grand

14. A Voice for the Voiceless

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

Photo Insert

Prologue

January 9, 2016

“When people speak of resistance in France, they speak very little of the women who were involved,” Michèle Moët-Agniel declared. “No one ever talks about the women!”

“There is a reason for that,” Anise Postel-Vinay (née Girard) exclaimed. “Women get into the war and then after it they don’t talk about what they did. Men love talking about war!”

The three of us had been having a lively conversation about what they did in the war for more than an hour by then. A sprightly ninety-year-old with a head full of silvery ringlets, Moët-Agniel hid downed Allied pilots before helping them out of Paris to safety during World War II. She was a teenaged schoolgirl in those days, and she was well aware that her exploits could land her in a concentration camp if she was ever caught. Postel-Vinay, now a bespectacled ninety-three-year-old grande dame, was aware of that risk too. But in her twenties that didn’t stop her from gathering surveillance on German troops and passing it on in matchboxes bound for London.

“The occupation was heartbreaking for us,” Moët-Agniel said. “It was intolerable.”

Knowing something is heartbreaking and intolerable is one thing, but having the mettle to stand up and do something about it is a whole different story. That’s why I asked—correction: I begged—to meet these two women, both of them resisters and friends of Geneviève de Gaulle Anthonioz. There aren’t many people like them anymore. So there weren’t many people better placed to tell me about Geneviève during wartime or give me a better understanding of what women like them faced in their fight to reclaim France from the Nazis and then rebuild their own lives at the end of the conflict.

“Don’t you think that story is important?” I asked Moët-Agniel in a near-desperate phone call a few days before our meeting was arranged.

“Oui,” she told me in her singsongy voice.

Within forty-eight hours of that discussion, Moët-Agniel invited me to a get-together at Mme Postel-Vinay’s twelfth-floor apartment, overlooking Paris. I brought them miniature red rose plants in gratitude. They treated me to tea, slices of flaky galette des rois, and a couple hours’ worth of their stories and insights.

“People remember the bravery of the Americans and the English,” Moët-Agniel said. “They don’t remember the people who helped the Americans and English.”

When Moët-Agniel was fourteen years old, she and her family fled Paris before German troops arrived to take over the capital on June 14, 1940. Three days later, the Moëts listened around the radio, horrified as France’s newly appointed prime minister Marshal Philippe Pétain announced that he had asked Hitler for an armistice. None of them felt this betrayal as profoundly as her father did, Moët-Agniel recalled. He had admired the elderly marshal for his heroism against the Germans in Verdun during World War I, so his capitulation to them more than twenty years later was incomprehensible, unthinkable. “We must do something!” Moët-Agniel remembered her father saying under his breath as Pétain’s voice crackled over the airwaves.

Five days later, the Moëts tuned in to the BBC and heard a young French general implore his country to keep up the fight. His name was Charles de Gaulle, and it was the second time in four days that he had addressed his countrymen from London, calling on their patriotism, common sense, and higher interests to liberate France from the Germans and restore its honor. It was the exact message the Moëts had been hoping to hear. When they returned to their home in suburban Paris a few weeks later and found the capital “disfigured,” their desire to “do something” was further reinforced. For many French men and women living during that summer of 1940, it was difficult to know how to respond to this indignity. As German forces fanned out across the northern part of France, many of the French walked a fine line between insolence and surrender in order to survive food and supply shortages, curtailed freedoms, and unknown fears. Conversations with friends and neighbors became more tentative, at least until you knew their stance on the occupation and national government, which had since moved southward to the spa town of Vichy.

Not all of the French were inclined to do something in those early moments, but that didn’t mean they were all resigned to accept their occupier’s dictates. Nineteen-year-old Geneviève de Gaulle, niece of that general whose commanding voice captivated the Moët family after France’s fall, began her resistance activities by turning her back on passing Nazi soldiers instead of saluting them. She did not believe France was truly conquered, so she would not submit to a victor’s rules. Twenty-year-old Jacqueline d’Alincourt ventured out each morning with her three sisters to post anti-Nazi posters around their hometown. They concealed their faces with umbrellas to prevent people from determining who was papering local buildings with these notices. Germaine Tillion, a thirty-three-year-old anthropologist, provided prisoners of war with new clothes and identities, hid Jews, countered German propaganda, and transmitted military intelligence to London, all through a resistance network run out of the museum where she worked.

“Even those who supported Pét

ain were anti-German,” Postel-Vinay said.

Moët-Agniel remembered the day her teacher visited her house after attending a large student demonstration, which was forbidden at the time. The protest was on Armistice Day—November 11—and early that morning an opposition group placed a wreath at the statue of Georges Clemenceau on the Champs-Élysées. On the wreath: a red, white, and blue ribbon and a calling card that was purported to be from General de Gaulle. The ribbon and the calling card mysteriously disappeared shortly after they were discovered, but soon armfuls of bouquets began piling up near the former French premier’s statue. By early evening thousands of students and teachers had gathered at the Arc de Triomphe, some of them placing bouquets at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, others shouting “Vive la France,” “Down with Pétain,” and “Down with Hitler” into the cool twilight. When fights broke out, the Germans responded by firing into the crowd, making more than one hundred arrests, and then closing off the Champs-Élysées. There in the Moët residence, they agreed that the state of affairs was unacceptable. But again, what could you do?

The answer presented itself to the Moëts a few days later when they received a large envelope full of pro-resistance tracts. They had no idea who had sent them to their house but noted that the mail was postmarked Versailles. Who did they know in Versailles? The mother of Michèle’s teacher.

“We quickly telephoned her to ask her whether she had written us,” Moët-Agniel said. “She said yes and asked if she could continue to write us regularly. So we continued to receive these tracts in the mail. We would copy them and distribute them everywhere. That’s how my family got into the resistance. We began by doing this, then this, then that.”

Postel-Vinay said she and her family would occasionally get their hands on some of the leaflets that were circulating. They were never signed. They had no address on them. So it was difficult to figure out who to contact about getting involved. She thought of going to England, but her mother would not let her do it unless she could find a travel companion. The companion never materialized, but Postel-Vinay’s mother eventually made contact with a philosophy professor who shared their views. Young Anise was put to work by an intelligence service that sought military information about the Germans.

“I feared I would not be up to the task,” she recalled. “Asking a nineteen-year-old to distinguish one tank from another? It was hard enough for me to tell a tank from a machine gun.”

Postel-Vinay would find her footing, just as the disparate elements of the movement would gain in numbers and strength. There is a certain cinematic quality to her tale: beautiful young woman on bicycle risks life gathering information for the Allies, all the while gaining confidence and pride in her abilities. Her accomplice at the time is a melancholy man with a marvelous command of English. His task: translating her reports before handing them to a photographer who would convert them to microfilm images. The photographer hid the film in a matchbox, then handed it to a young woman tasked with sneaking it to the British consulate in Lisbon.

“I didn’t learn this [translator’s] name until ten years later,” Postel-Vinay said. “All that time, I had been working with [Irish writer] Samuel Beckett!”

* * *

The best way to sidestep a conversational minefield with a surviving member of the French resistance is to avoid questions about the movement’s size and impact. It’s sensitive territory that is the subject of much historical debate. First, there’s the issue of the movement’s size, which depends on how resistance is defined. For some it means blowing up railroad tracks, joining militias, gathering military intelligence, editing and distributing underground newspapers, or hiding downed Allied pilots. By these standards an estimated two hundred thousand to five hundred thousand people in a nation of thirty-nine million could claim to have taken part in the fight. Others characterize resistance in broader terms, such as refusing to speak to the German officer stationed in your house, reading a Gaullist tract and sharing it with your neighbor, lying to the Gestapo about your friend’s whereabouts, or tearing down a Nazi flag. At least two million French men and women become resisters when considered in this way.

No matter the estimate, statistics suggest that a small percentage of the population was pushing back against their Nazi foes. This has raised thorny questions about what the rest of the French population was doing and thinking and why. Some believe the vast majority waited out the war and survived daily tribulations as well and as peacefully as they could. But Charles de Gaulle argued the country was united in resistance and perfectly capable of liberating itself with a bit of help from its Allies. “A handful of wretches” collaborated with the enemy, he said. Some historians have called his claim the “Gaullist myth,” pointing to the small number of confirmed resisters and claiming their actions were never serious or organized enough to save the country from the Nazis. Documentaries such as Marcel Ophüls’s The Sorrow and the Pity have suggested that perhaps more French citizens collaborated than resisted.

“There was a movement of historians and intellectuals that said the resistance was not much of anything,” Postel-Vinay said. “This was to harass de Gaulle because he was never one to make up political stories. He was someone who was attached to the truth. Even today, history books contain the fable that the resistance was next to nothing and people remain attached to that idea, even though it’s not true.”

Another body of research has emerged—some of it by Postel-Vinay’s daughter, the historian Claire Andrieu—that has affirmed how broad the movement was and illustrated how important it would become to France’s postwar politics. The general’s vision of “one France” inspired a shattered and fragmented country to rebuild and become great again. Andrieu has argued that plenty of people within France helped resisters in a variety of ways and quietly thwarted the Nazis. They may not have been officially classified as resisters, but their collusion with the movement was a sign of their ultimate support for what it represented politically.

For Geneviève de Gaulle and the women in her orbit, the resistance was all too real, and it played a profound role not only in their country’s future but also in shaping their own destinies as young women in a largely patriarchal society. Although they had not yet gained the right to vote (that would come in 1944), some women elected to demonstrate their devotion to France rather than accept its defeat. Moët-Agniel, for example, began sneaking into the northern part of the country to retrieve downed Allied aviators and bring them to Paris. Once in the capital, she found her charges civilian clothing, false identity documents, and shelter until they could obtain transportation into southwestern France. As soon as she secured their travel, Moët-Agniel escorted pilots through the city to a contact who was waiting for them in the Jardin des Plantes. This contact ushered the aviators to a night train that chugged toward the Spanish border. Upon arrival, the flyers were entrusted to another contact who helped them cross the Pyrenees on foot into Spain and safety. Completing a mission like this took great presence of mind, and male resisters soon found that women in their networks had a knack for improvising when placed in pressure-packed situations. One German prosecutor mused that if the French army had been composed of women and not men, the Nazis never would have made it to Paris.

And yet nobody talks about the women. When the Germans either captured or demobilized one and a half million French soldiers in June 1940, women stepped in and worked with men to create some of the country’s first resistance networks. Although women rarely assumed leadership roles in these organizations, they did become essential links in the movement, working wherever and whenever the need was greatest. At the beginning of the war, they were rarely suspected of being up to something. Charming smiles concealed true motives, at least until German informants began infiltrating resistance networks. By 1942 some résistantes began getting the much-feared visit from the Gestapo that brought their heroism to a temporary halt.

One such patriot was Geneviève de Gaulle. Geneviève’s story has lingered in

her uncle’s considerable shadow, in part because no one ever talks about the women, as Moët-Agniel said. As the general inspired his homeland from afar, his niece fought for France on the ground, risking her life as she carried messages to resistance contacts, spread Gaullist propaganda, and wrote for a prominent underground journal. Like her uncle, Geneviève had a way with words and a flair for public speaking. Yet his speeches were prepared, while hers came straight from the heart. It was her heart that propelled her toward the resistance, after all, fueling her activity in the movement and inspiring the people she met along the way. Geneviève knew she could be arrested and tortured for her endeavors, but that knowledge never stopped her from her work. She carried important resistance documents over mountain ranges, distributed illegal newspapers in plain view of German officers, and juggled false identities to suit her situation. Her luck did not last forever, but courage and camaraderie would carry her through what would become the darkest time of her life. She would survive that trial and use the experience from it to play a singular role in her country’s postwar politics.

To those whose lives she touched, Geneviève de Gaulle was a hero, but she abhorred that label and the attention that came with it.

“I don’t like the word heroism,” she once told French journalist Caroline Glorion. “And I don’t think that we should seek to have a great life or grand destiny. I think we should seek to do what is right.”

Geneviève’s life was marked by her unflinching desire to do the right thing at the right time for other people, Postel-Vinay said.

“She had extraordinary compassion for other people,” Postel-Vinay said. “When someone was in need or in bad circumstances, she realized that something needed to be done and she did it immediately.”

Moët-Agniel added: “She would say, ‘Yes, I am a de Gaulle and it opens doors for me,’ but [when those doors were opened] it was always so that she could serve others.”

The General's Niece

The General's Niece